This is the third of my

review reports on COVID-19 worldwide as at August 20th 2021. This

report will cover transmission of the virus. I’ll be looking not at cumulative

cases or daily new cases, but at the (weekly) rate of growth of new cases. I’ll

also be looking at the R-rate, which is defined as the average number of new

infections resulting from one infection.

Conceptually, there are

some differences between weekly case growth and R-rate. Firstly, weekly case

growth is based on measurements of new cases (I calculate the weekly case

growth as the weekly percentage growth in new cases counts which are already

weekly averaged). R-rate, on the other hand, is based on using an

equation-based model to estimate infections. The methodology for calculating

the R-rates supplied by Our World in Data is documented at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3581633.

For the R-rate and weekly

case growth to correlate well requires not only that the model is accurate, but

also that the proportion of infections which are not detected as cases is

constant. The graphs for individual countries in the first two papers show that

the two statistics do correlate quite well, at least since the first three or four

months of the epidemic; and thus, suggest that these assumptions are valid.

Europe

Here are the weekly case growth and R-rate graphs for the

four regions into which I have divided Europe:

The weekly case growths seem to be a lot more volatile than the R-rates, particularly in smaller countries. Weekly case growths are also seriously perturbed whenever there is an adjustment made to the case data of a particular country. That said, when the R-rates are in their mid-range of approximately 0.5 to 2, they do seem to correlate well with the weekly case growths. Because of this, for the rest of the world I’ll only show the R-rate graphs.

One notable feature of the above R-rate graphs occurs where

several countries have suffered sudden, sharp rises in their R-rates at much

the same time. A good example is the precipitate increase in many of the Europe

14 countries starting around the middle of June 2021. The sudden and almost

parallel rises in many countries suggest that this may have been down to the

spread of the, relatively new and more transmissible, delta variant. In the

previous few weeks, the UK and Portugal had been above the others in the

general level of R-rate; and they were less affected by the subsequent spike,

suggesting that they may have received the delta variant earlier than others.

In Eastern Europe (North) there was a similar spike, a

couple of weeks later. Russia, Moldova and Belarus were the three countries

above the others in the previous few weeks; but all three had sudden rises in

R-rate during June. Might the new variant, in this area, actually have spread

from east to west? In the southern part of Eastern Europe, virtually every

country has been affected by a spike in R-rate in late June or July, though

Cyprus had it first by several weeks. Malta also had a big spike during June.

Americas

In North America, there are strong increases in R-rate in the USA starting in June, and in Canada a little less than a month later. That dark brown line at the bottom, Nicaragua, doesn’t look right to me.

South America does not show any precipitate increases, except for Suriname which, having a population of only 600,000, is always likely to show up as more volatile than larger countries.

In the West Indies, those recent spikes in Antigua and Barbuda (mid blue) and Saint Kitts and Nevis (dark brown) are reminiscent of the spikes in Europe. And the recent R-rate figures for Dominica (light blue) and Grenada (dark blue) don’t look right to me, given that Dominica has had a big spike in cases starting in early August, and Grenada (a country of only 100,000 or so) a smaller one.

Middle East and North Africa

Not much to see recently in the northern Middle East, except for the recent strong rise in the Lebanon.

In the southern Middle East, there has been a big rise in Israel starting in June, and another a few weeks later in Palestine. Delta variant, perhaps?

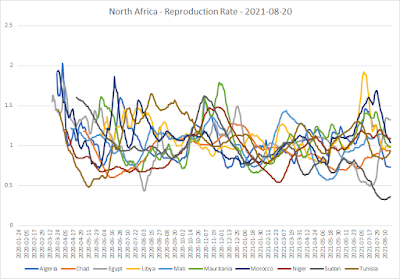

In North Africa, there were big recent rises in Libya, Morocco and Egypt. Could the delta variant be spreading on the North African coast too?

Sub-Saharan Africa

In Central Africa, the R-rates are generally lower than in other places, and are frequently below 1. They are also very variable. It looks as if the virus has difficulty spreading in central African conditions; perhaps because of the heat and humidity? And there is no co-ordination between the R-rates for the different countries, possibly reflecting a relatively low amount of international travel.

The four recent peaks are in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique

and Mauritius. There was an earlier peak, starting from a much lower base, in

Eswatini too. The straight, steep rises are reminiscent of some of the European

R-rate graphs. Except for Mauritius, I would guess this could be the signature

of the spread of the beta variant (originally found in South Africa), which

like the delta variant is highly transmissible, into these countries. It’s

possible that some of the rises in East Africa might be due to this, too.

Here, the recent peaks come from Liberia, Sierra Leone,

Senegal and Nigeria. Could there be some more transmissible variant of the

virus spreading between these countries? If so, it seems surprising that I can’t

see anything untoward for other countries in the area, such as Ghana or Cote d’Ivoire.

Rest of Asia

In East Asia, one thing to note is that enormous R-rate in South Korea (light blue) at the beginning of the epidemic. What happened there? Was that a variant that no-one else got? Another thing to note is the three recent peaks in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. Taiwan and Japan’s peaks were probably down to the delta variant; could that have been so in South Korea too?

The recent rise in Azerbaijan (light blue) might possibly be an effect of the delta variant?

I wonder whether India, Nepal and the Maldives in mid-June, and Sri Lanka in early July, may have received a more transmissible variant – such as the delta?

The big, sudden recent spikes in Laos and Singapore may well be due to the delta variant.

Oh, and why was the R-rate in Singapore so low as far back

as the end of February 2020? As far as I can see, no-one else in the world

except China had such a low R-rate that early. If that’s right, they must

have had an earlier wave! But their cases continued to grow through February

and into March. So, the correlation between R-rate and weekly case growth was

broken at that stage of the epidemic in Singapore.

Australasia and Oceania

Australia seems to have had as many separate R-rate peaks as anyone in the world. And New Zealand, after the initial outbreak, seems to have kept its R-rate consistently as low as anyone outside Central Africa. (Up till August 20th 2021, of course).

Some examples

I decided to pick some countries I haven’t looked at in

detail before, which show different behaviours in epidemic profile from their

neighbours. I chose: Germany (lowest cases in its area). Russia (a big country,

where the virus may well spread differently from its neighbours). Cyprus (an

island with high cases, out of sync with the rest of its group). Nicaragua (can

I really believe how few cases and deaths they have had?). Pakistan

(unexpectedly low cases for its area). Saudi Arabia (ditto). South Korea and

Australia (both having multiple peaks of different sizes). And New Zealand, to

compare with Australia.

Germany

Russia

The Russian epidemic is, necessarily, on a large scale, and it tends to move more slowly than in other places. Nevertheless, there have been substantial bumps in the R-rate in September/October 2020 and in early June 2021. The latter is probably due to the delta variant. There is some doubt over the accuracy of the Russian statistics; it’s said in some quarters that both cases and deaths have been under-estimated. If true, that could prove to be an advantage from this stage of the epidemic onwards!

For much of the time, Russian lockdowns have been

relatively light; particularly since many of them have been regional only. The

recent surge in cases has prompted a reversal, but the lockdowns are still less

than in many countries further west. It’s worth noting that the Russians have

kept on moving between quarantining international travellers, banning some of

them, and from March to July 2020, closing the borders entirely.

Cyprus

Cyprus has had several big peaks in the R-rate, two of them being in midsummer. It held cases down until October 2020, at which point cases rose towards the first of three peaks. The most recent peak has the signature of the delta variant, and suggests that Cyprus was one of the earliest countries to get it. The R-rate is now below 1, and Cyprus looks to be in better shape than most other countries in its region. Lockdowns have been gradually relaxed, and the only mandates remaining are screening of international arrivals, a medium restriction on gatherings, and face coverings required when with others.

Nicaragua

When I first looked at Nicaragua’s figures, I didn’t believe them. I still don’t believe them. The reported cases per million are extremely low for the region, only 0.16% of the population; and only 1.9% of these have died of COVID. Cases and deaths are only being reported weekly, and the recent deaths per case ratio, if I could believe it, would be outstanding compared with its neighbours, at 0.28%. The reported death counts each week have been exactly 1 for the last seven weeks in a row. The lockdowns have been consistently among the lowest in the world. The R-rates since the new year don’t make sense at all. In short, no lo creo.

Pakistan

Pakistan’s recorded cases count is very low compared with countries around it (other than Afghanistan); only 0.5% of the population. Lockdowns have been consistently high, with an average stringency of 63% throughout the epidemic, and a current stringency of 67%; but, because Pakistan is a big country, many lockdowns have only been regional, and some regions may have got off more lightly. The last week of July 2021, which saw a big surge in cases yet only a small increase in the R-rate, suggests that a lot of the population are still in the “susceptibles” category. This is corroborated by the vaccination levels, with only 5.5% of the population fully vaccinated. So, Pakistan still has a long way to go.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, like Pakistan, has low cases per million compared with most of its neighbours. Lockdowns have been high, particularly during the first wave. It would seem that this is what got the Saudis to their relatively low cases per million. There has been a very gradual series of unlocks, but the average stringency throughout the epidemic is close to Pakistan’s at 62%, and the current stringency is 54%. The Saudis are better off than Pakistan, particularly since they have managed to fully vaccinate 33% of the population. But they, too, still have a long way to go.

South Korea

South Korea’s total cases are 0.46% of the population, way below European levels (about a tenth of Germany’s). They locked down early – closing schools in February 2020. And they locked down hard – mandating stay-at-home and travel restrictions, and closing some workplaces, in the third week of March. Lockdowns have averaged 54%, and are now at 51%. But the delta variant seems to have caught up with them in late June and early July 2021, and their cases are now at their highest point so far, 35 new cases per million per day – though still low by European standards. They have a long way to go to reach herd immunity! And only about 20% of the population are fully vaccinated, so they have a long way to go on that score too.

Australia

Australia’s cases per million are even lower than South Korea’s, at 0.17% of the population. And like South Korea, the delta variant has recently caught up with them, and propelled new cases to previously unseen heights. But unlike South Korea, the R-rate doesn’t seem to want to come down again; despite recent lockdowns. Like the USA, Australia is a multi-state country, so the stringency (averaging 58%) will often overstate the actual lockdown severity. But Australia’s biggest lockdown is a national one: the borders have been closed since March 20th 2020. It looks very much as though they may now be finding themselves in a Uruguay situation, of a good start followed by a big spurt of cases. Their vaccination levels are similar to South Korea’s, so the vaccines aren’t going to save them – not in the short term, at least. Their early successes, I think, may turn out to have been a shot in their own foot.

New Zealand

The New Zealanders closed their borders on the same day as Australia did, and have kept them closed since. If it wasn’t for that uptick at the right-hand end of the cases graph, this would look like the perfect strategy – wouldn’t it? Lock down hard to get rid of the first wave, then keep lockdown levels generally low (averaging 35%), while zapping the virus occasionally with targeted lockdowns to keep cases down. Unfortunately, that uptick looks very much like the arrival of the Dreaded Delta. As at the time of writing (August 29th), new cases had gone up by a factor of 5 inside a week. Vaccination levels are similar to Australia’s; so now, they’re both together in the same pickle. It will be interesting to see how the New Zealanders play things from here.

To sum up

The weekly growth in new cases, and the reproduction rate (R-rate)

estimated by use of an equation, correlate well with each other, at least after

the first few months of the epidemic.

The “signature” of the delta variant is even clearer in the R-rate than it is in the daily new case counts. Particularly in Europe, many countries have seen sudden increases in the R-rate, moving successively from country to country. These now seem to be extending to more and more parts of the world. There are similar signatures in some countries in Southern and East Africa, which may well be evidence of spread of the beta or “South African” variant. And there is something transmissible spreading among some of the countries in West Africa, too.

As to the countries I picked for further detail: Australia and New Zealand appear to have had their entire strategies against the virus thrown into confusion by the arrival of the delta variant. South Korea is in a similar situation, if maybe a bit less serious. Saudi Arabia and Pakistan have achieved their relative success so far by hard lockdowns; but there isn’t any evidence the delta variant has reached them yet. Ouch!

Nicaragua’s figures are not believable. Cyprus, right now,

looks as close as I’ve seen to having dealt with the virus both successfully and with

at least a modicum of concern for people. Russia is… Russia. Enigmatic, and

maybe dealing with the situation better than some think. And Germany is…

Germany. I suspect they’re in a similar situation to the UK: not out of the

woods yet, but with some open country apparently visible in the distance.